Poetry Winter 2022 fiction all issues

whitespacefiller

Cover

Li Zhang

Ana Reisens

Pam asked about Europe

& other poems

Krystle May Statler

To the Slow Burn

& other poems

Kristina Cecka

On Remodeling

& other poems

Belinda Roddie

Bless The Bones Of California

& other poems

Summer Rand

Alexander tells me how he'd like to be buried

& other poems

Alexander Perez

Toward the Rainbow

& other poems

Karo Ska

self-portrait of compassion…

& other poems

David Southward

The Pelican

& other poems

George Longenecker

Stamp Collection

& other poems

Mary Keating

Salty

& other poems

Talya Jankovits

Imagine A World Without Raging Hormones

& other poems

Laurie Holding

Sonnet to Mr. Frost

& other poems

David Ruekberg

A Short Essay on Love

& other poems

Elaine Greenwood

There’s a thick, quiet Angel

& other poems

Richard Baldo

Carry On Caretaker

& other poems

Jefferson Singer

Dave Righetti’s No-Hitter…

& other poems

Diane Ayer

A Fan

& other poems

Kaecey McCormick

Meditation Before Desert Monsoon

& other poems

Meg Whelan

Resubstantiation

& other poems

Katherine B. Arthaud

Possible

& other poems

Aaron Glover

On Transformation

& other poems

Anne Marie Wells

[I'm crying in a sandwich shop reading Diane Seuss' sonnets]

& other poems

Holly Cian

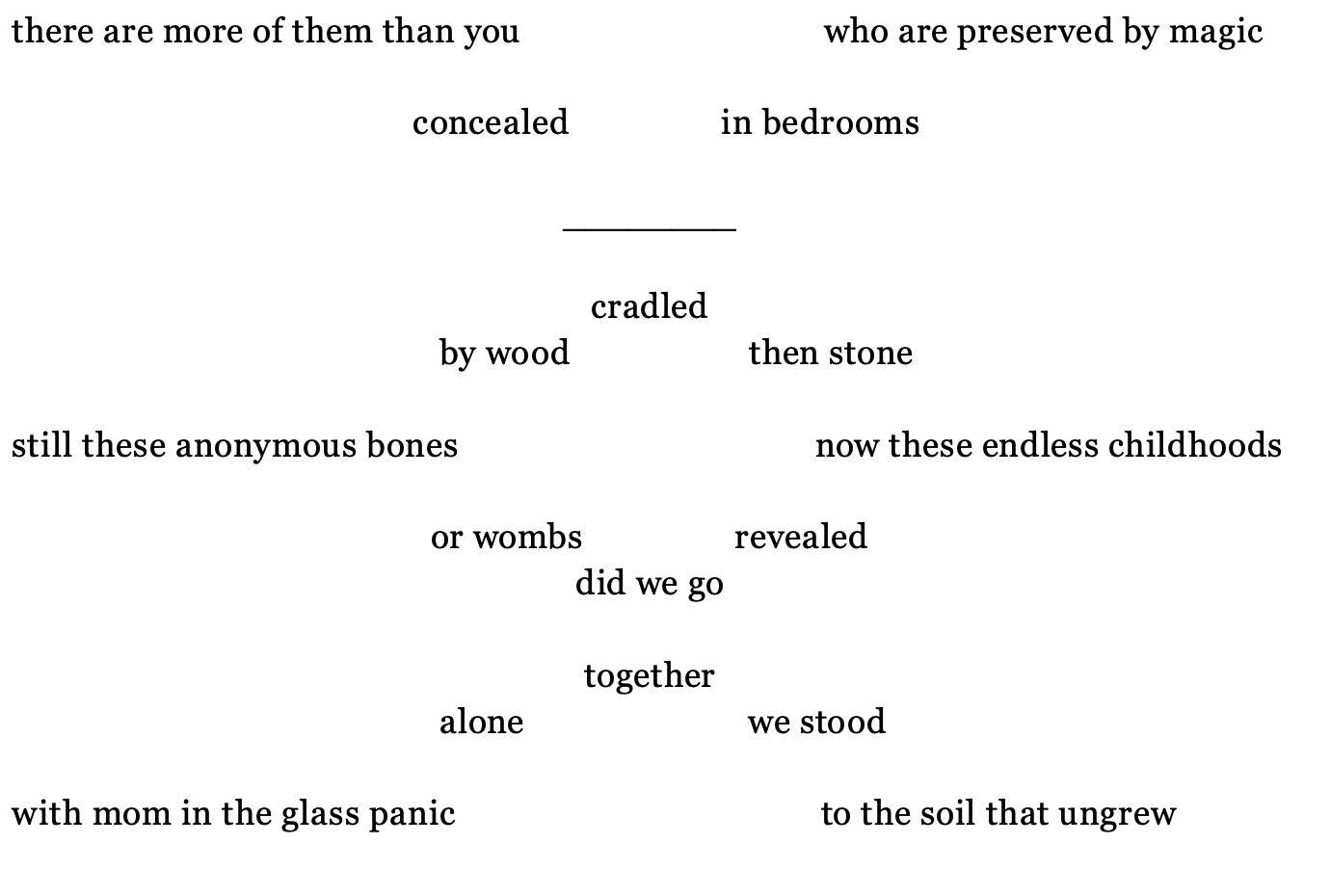

Untitled

& other poems

Kimberly Russo

Selective Memories are the Only Gift of Dementia

& other poems

Steven Monte

Larkin

& other poems

Mervyn Seivwright

Fear Mountain

& other poems

Meg Whelan

Resubstantiation

I was happy to feel that blood.

I knew it was here, swollen and warm,

the way I knew it was there, drying,

when they called to say he was missing

with a gun

Could you please try calling him?

Yesterday’s ache of growing Texas martyrs

became pain that pulsed

and gripped the steering wheel when

I braked long enough to feel

Thank God

I’m not pregnant

in Kentucky

I can’t get a hold of him.

The one degree of separation that kept their hands clean

I’ll press between their palms

like a prayer stone

with the sharp end facing bone and staring through

skin with a scream

They’re looking.

I hope their veins stigmatic stream

until the pools drown each gesture in the lives

of those they took

I hope their fingerprints last

and that their legacy

sinks them deep

So when my thumb is gripped by a little hand,

instead of this welcomed red,

her body is proof of a reckoning

until we send her to school

I’m sorry.

Cocoon

The first who arrived on line twelve, her in the fur and him in the black,

both with socks which suited shoes that belonged on streets,

arms across one plastic seat

and in kerchiefed pockets as he stood,

not even a nod the stop, eyes ahead and past the glass.

At dinner, there were just two wings—orange oozing to a blur—circling

around the three below. I figured that the butterfly had arrived

with the front yard’s fresh daffodil patch. And that it had snagged

adventure in the whirl of the ac unit. I watched on the other side.

And then him, with crutches, and her

with chestnut hair holding her hips,

who smiled to pull in close,

like the three-quarters mark of a movie,

and she left, flicking the door open, not seeing

if he fluorescent followed behind.

After my walk, the two became six. I poured a glass to drink. Now,

eight? Ten? Like water in hot oil, the frenzy pumped their bodies into

and against and with the cyclone. They were at the whim of seventy-

one degrees.

Now them, who let masks hang and chair fling upright

to press into each other, him petting the bridge of her nose,

her checking their reflection in the smudged poster beside my head,

as a shove hurdled them into the next.

The sun set, the house cooled, and the thermostat stopped. And the

breeze-climbing couples made a dash into the fiery shadows of dusked

trees. I watched them quiver in the pine limbs until night turned the

window into a mirrored face.

And metal released from our embrace,

and I danced down the hill because my body said so,

elbow pushing through evening winter air, inviting

fingers to a sweet flourish at the peak,

falling again as my feet told me to turn.

She takes her bow. And becomes my home.

Pennebaker said that if you write, you go to the doctor less // Water is healing

I bet those sideways scribbles were like morning’s first faucet sip.

We didn’t think to need it, but it sure did feel good

when the pen straddled nubby fingertips and puffy palms

like a colander balanced between big pot and frying pan.

It’s important to stay hydrated.

She placed me at the afterdinner table with marker and laminated alphabet

like a mutt pup thrown to the lake because he surely knows how to swim.

His flails and gasps breed confidence after his bones teach him how.

Mom was glad the ink wiped away dry.

But still, she warned the kindergarten that I’d taught myself and that I

was proud. And from his tank beside the bookshelf,

the box turtle slammed against the glass. The splash held my gaze

while I dazed at dotted lines and trained fingers for form.

The cartons of the journals downstairs in the hot water closet.

Pound for pound, how many of them would represent surgeries unstarted, scars unslit, organs unautomized, molecules unmitigated?

If he had just written rather than sinew-strain, how far could he have been saved?

If he had told us earlier, if he could, would my text box sit alongside his buried one?

At what point across the ocean does a keyboard activate?

And what happened, then, when a few fell out drunk

in a room of a million languages?

What good did it do?

Your body is 70% water.

Why’d you like the mummies?

For “woman (35-49 years)” and “young . . . dynasty”

at the British Museum.

Romantic

We called that pretty, and it stopped them,

but shaken centimes in cardboard cups couldn’t.

Pink puffs of cotton candy cloud

painted in backward portraits while

the real thing brewed over cigarette butt huts,

and I walked down it while the brush

stopped to ask quelle heure est-il,

but the concrete drying kept me from

translating, so I showed her the phone

which, in English, showed me as I was,

and my lover’s hand who held his own

sunset zinnia which I gripped in palms

that were freshly picked by paranoia.

You displace what’s

in front of you

to see less clearly.

Meg Whelan is a Kentucky writer and teacher living in Paris, France. Her friends describe her as someone who “treats life like a university class.” Her poetry focuses on themes of embodied grief and shared memory. You’ll probably find her reading in the corner of a metro car, dancing on upward moving escalators, or frantically scribbling down other people’s life events in her calendar.

is a Kentucky writer and teacher living in Paris, France. Her friends describe her as someone who “treats life like a university class.” Her poetry focuses on themes of embodied grief and shared memory. You’ll probably find her reading in the corner of a metro car, dancing on upward moving escalators, or frantically scribbling down other people’s life events in her calendar.